Note:

July 22, Oakland, sunset.

Note:

July 22, Oakland, sunset.

This piece was originally written in May 2000, before my trip to China

that year. Now in the following July, I am able to finish editing

and gathering the images. All but one of the images are from Jean’s

own work, one is mine made the last few weeks to honor hers and/or to take

the place of one of hers that is now lost or unavailable. Each image

is marked accordingly.

As

I began to work this evening, an old song came to mind, suggested partly

by the time of day, and partly by the work that I am doing...

In the gloaming, oh my darling...

Softly come and softly go...

The

late low sun shines through the dining room window; the chandelier glows

with sunset light—that light, that moment always so beautiful for me, that

light and moment so filled with the essence of our home here together,

mine here now. (Stephanie has somehow never taken dwelling here, nor

have I in her place in Montreal. Last month when she was here for a

few days, I showed her that summer sunset light in the dining room

chandelier and said, “I think it is very beautiful.” I did not speak

of the emotional bonding it represents for me.)

In

the gloaming oh my darling softly come and softly go these thoughts about

your art that I wrote more than two months ago and of which I will tonight

complete the edit and illustrations.

*

I had met Jean in the basement of the Art

Department in the fall of 1948. She had just returned from summer at

an artist's colony on the shore of Lake Aijiji in Guadalajara. She

was exotic and of the south. I felt myself to be of the north, and

the attraction between us was mutual and total.

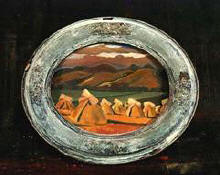

Jean

Martin: Untitled (Havest)

Jean

Martin: Untitled (Havest)

Oil on canvas board, approx 9 x 12 in.

Jean continued to paint in the first year after we were married. I

loved her paintings... of which only a few have survived plus one more as

a slide. The earliest of the survivors is a small landscape painted

before we met. Fields, shocks of grain, purple hills in the

distance. I framed it in an oval frame left over from someone's

1900's portrait, painting the brown frame white and then glazing it with a

bluish purple like the one Jean had used for the mountains at the back of

the fields in the painting. Jean told me that Auntie's boyfriend's

sister Flo had questioned her about it and had dismissed it as a "daub."

Then Jean stopped painting -- I guess until we met.

Jean

Martin: Tree

Jean

Martin: Tree

Oil on canvas, 36 x 24 in.

The second painting of Jean’s that I have from before we were married was

made in the

Art

Department in the fall of 1949. It is of

the old fruit tree outside my room on

McAllister Street in San Francisco. It shines with the light of our

morning lovemaking in that room.

Thinking now, I remember a third

painting of hers from that time that I still have... enamel on panel (in

those days, we all used enamel from the hardware store), a couple of

large, strange forms in simple colors, and one small black form sticking

out like a scorpion's sting.

I don't think Jean painted anything

during our six months in the Studio Gallery, but after that when we were

painting in the loft of the old dairy (in Berkeley and near the campus!),

she began work on an immense canvas (four by six feet?), a slough she had

seen northwest of Vallejo with an old ferry boat docked there. While

she was working on it, she also made some still life paintings and some

little drawings and watercolors. I still have one of the still lifes.

Another one, the best one, she gave to J. DeFeo the week that J. lived

with us after her breakup with Wally Hedrick and before she moved to Ross.

It was in the mid 1960s. I gave J. a little portfolio of pencil

drawings of poppies, and the tall black “landscape" from 1948-49.

One Sunday morning a year

later, I decided we had to go to see the sunset at Pyramid Lake in Nevada,

and that we should go to Ross first to see J. Jean, Tony, Fredricka

(and Demian?) and I drove to J.'s. Jean's still life was under the

kitchen sink; the pencil drawings from my portfolio were scattered in a

heap of wastepaper in the living room; and the tall black landscape was

outside leaning against a tree, the sprinkler system for the garden

finishing in the summer what the winter rains had begun. Hours later

we got to Pyramid Lake in time for the sunset -- it was a silent and

beautiful slow dying rose on the peaks and cliffs to the east as the water

before us sank through turquoise to night -- and then we spent the night

driving home.

Jean Martin: Ferry Boat, 1950

Oil on canvas, approx 48 x 72 in.

But back to the big painting of the

ferry boat in the slough (I have read enough Jung to see the watery,

grassy slough as the unconscious and the ferry as the Self on its

journey), and the little watercolors Jean was also making that I never

saw. Sam Francis had found the old barn of dairy for a studio, and

we shared the loft with him. Jean had made a little watercolor of

mushrooms in the dawn. Sam sneered at it as—what were the words?...

paltry? women's stuff? trivial? worthless but typical?... Jean never

painted again.

Jean saw and loved the small things at

our feet. I looked only for the cosmic signs beyond the horizon.

I never knew what Sam looked for except "fame and the love of women” for

whom in the classic phrase of my high school years, "He’s 4F—Find 'em,

feel 'em, fuck 'em, forget 'em."

Those little things at our feet: bugs

and leaves, flowers, mushrooms, all manner of the small things—and animals

too, we always had a dog or two that wandered in and needed love—those

were her care. And somehow too often in all the years we were

together, each time her need for expression reached out to speak her love

for the fragile beings in the world, some boor (male or female) like Sam

trampled them to death.

Those little things at our feet: sometimes

I too looked down and saw. But I did not see the fragile shining

things that give sentiment and beauty to life. No, I only saw the

cracks in the sidewalk and the dirt in the gutter, the dark horror that

mirrored my own irrevocable sense of sexual guilt and despair. A few

years after our time in the loft over the dairy, during my brief yellow

ochre plus pthalo blue plus cadmium red figure painting period, I also

painted a still life of what I saw at my feet. I destroyed it soon

after painting it, but memorialized it as the frontispiece in my

"Dirt in the Gutter" booklet of 1987. I wish now I still had the

original painting, but most of all I wish I had the little watercolor of

mushrooms in the dawn, because that was what we were then, tender beings

growing up out of the darkness and seeking the sun.

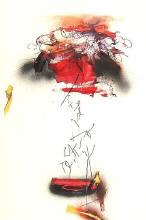

My

#16 July 2000,

My

#16 July 2000,

Untitled after Jean’s mushrooms (my third try)

Acrylic on paper, 30 x 44 in.

People in art education sometimes excuse their clumsy and vicious

diatribes at student's expense by saying, "If they can't stand up to it,

they should give up now." Sam Francis was never an educator, and I

don't think he would have excused himself that way even if he were.

He was always too busy building his own ego to notice that its

aggrandizement was due to his denigration of those around him.

Jean did not paint again. After

almost a year she moved instead into an area of visual expression no one

around her had used at that time and so could not hoist themselves by

belittling her. She began to make what we now call "constructions,"

that is, assemblages of found objects which can become symbols quite other

than the miscellaneous fragments from which they were constructed. I

remember that my father, seeing her interest in putting these things

together, gave her some tools to do it with. The object I remember

that she made was a boat—the sail a vertical scrap of woven wire net, a

random piece of wood for the hull, a dowel for the mast and a tangled

strand of hemp rope to hold it all together. I thought of it then

and remember it now as our ship for sailing among the stars.

The ship and all the other projects

like it were soon lost in the chaos of the pregnancy and birth and infancy

of Demian. I finished my work for the teaching credential in June

1951; Sam moved to

Paris to make his fortune in the great world a month or two before; and we

moved to Maxwell for my first teaching job in late September.

The Maxwellains thought we were an odd

couple, and to prove it one of our friends in

Berkeley sent Jean a letter addressed to the "Contessa

Fisette di Martin." When the Post Office Lady finished telling her

friends, the whole town knew Jean was an Italian war-bride. The

local Lady's Aid Society had already invited her to one of their Women's

Afternoon Teas. After the letter, they never invited her again.

(Meanwhile, the men of the town had already decided that I would not do

for their weekly club meeting in the room over the corner bank. One

of them once apologized to me because, "you know, it just wouldn't work

out.") And so, we were ostracized. I painted every night in the

garage of our house (how cold in the winter!); while Jean played a lute

and sang folk songs in the living room. The need for self-expression

never stops.

Jean

Martin: The “Family Altar under the Redwoods,” with The Egg

of Night on the left (that’s a winged heart on the inside), and Mom’s

Apple Pie (the coffin) on the right.

Jean

Martin: The “Family Altar under the Redwoods,” with The Egg

of Night on the left (that’s a winged heart on the inside), and Mom’s

Apple Pie (the coffin) on the right.

Ceramic.

When we returned to Berkeley in 1954 and then moved to Harrison Street in

1955, Jean began to work in ceramic sculpture, taking a night class with

Stephen de Staebler at SFAI. I still have the apple box of

Hesperian Fruit, The Grand High Inquisitor (Jean’s grandmother,

mother and aunt all rolled into one hooded monk), her Mom’s Apple Pie

in the shape of a coffin, her coffin with lid as a masked Head of

Medusa, her Tortoise that Turns the World, her Egg of Night

[a winged heart] Fertilized by the Wind, a Dragon-Salamander to

go in front of the fireplace (it got too hot and cracked in two), and

assorted fragments in the manner of bits Roman sculpture patched into

Renaissance walls.

Fredricka was born in 1956. Soon

it was not possible to have the time to take night courses at SFAI, and

soon the creative drive that made all those ceramic pieces was drowned

once more in the chaos of the daily life of children, jobs and family.

A few years passed and we moved to Monte Vista in October of 1959.

Tony was born in May of 1960, and the possibility of creative work in art

further submerged.

By then, Jean was Curator at the

California Historical Society, and all her creative energies went to

building the collection, preparing the first significant show and catalog

of the collection, and then organizing the first (and only) big

fund-raiser event the Society ever had—“A Night on the Barbary Coast,” a

huge block party on Pacific Avenue and Gold and Sansome Streets with movie

star guests and the just beginning topless joints as draws.

The party was a big success; it even

made money for the Society. Shortly after, Jean was offered the job

as Registrar at the Oakland Museum of History, under Henrietta Perry as

Director. By all accounts, Henrietta was a complete nut, the kind

who stays in civil service jobs forever because no one knows how to get

rid of them. Soon enough, all Paul Mills’ efforts at the

Oakland Art Gallery to build a new museum for himself bore fruit.

However, the new museum would include not only art, but also history and

science—and Paul would not be Director. A consultant, Alan McNab,

the Director of the Art Institute of Chicago, was selected to advise the

museum board on how to proceed and what to build. He chose Jean as

his adviser for design and development of the history section, and then

offered her the job of Registrar at The Art Institute of Chicago. In

order to get her, he offered me the job of Head of the Design Department

of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

We both declined—by

that time I was Administrator of the Art Bank (the position is now

Director of Exhibitions and Public Programs) and Executive Secretary of

the San Francisco Art Association; and Jean had been promised the job of

the Curator of the History Division once they got rid of Henrietta Perry.

They did get rid of Henrietta, but gave the job to Tom (I no longer

remember his last name). Jean was a woman with a BA in Art; Tom was

a man with an MA in Anthropology. Jean left the museum world, saying

never again would she have a job where if you decided to leave there were

no other nearby jobs you could go to. She went back to school at

Merritt College, got an AA in Computer Science, and then a job teaching

computer science at a local trade school run by Control Data, then big in

the world of information, now I think long gone. She stayed at

Control Data, teaching 5 hours per day five days per week with a two-week

vacation until the mid 1970s when, once again, she was passed over for the

Directorship in favor of a man with less experience. She resigned

and went to work for Del Monte Corporation as a programmer, then systems

analyst, then Manager of Information Services.

Jean

Martin: Babies in the Sky

Jean

Martin: Babies in the Sky

Collage, approx. 10 x 6 in.

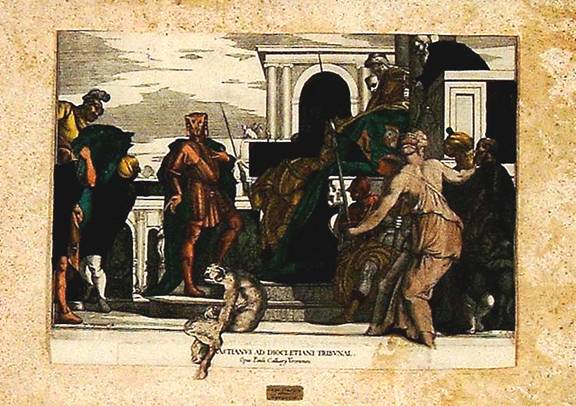

About Jean's art during these years. Those 1950’s years at the

Oakland Museum were the years of ceramics. During the years at the

Historical Society, the development of the Society’s collection and the

public world became her creative focus... although she began to make

collages from pieces cut from 17-18th Century engravings of

famous paintings. I still have many of these, made during the

Control Data and early Del Monte years. Jean entered these in juried

exhibitions, being accepted once but usually not—after all, it was the

days of late Pop and early Conceptual. During the later years at Del

Monte—late 1970’s and early 1980’s—Jean began to make tapestries and also

what were regarded as quilts. She entered these in quilt, fabric and

textile exhibitions—surely there would be no men in quilt exhibitions to

shove women and sewing aside as being "paltry, trivial women's stuff."

We were, however, in the period of "creative" textiles, when women

rejected women who did not weave tree branches into their tapestries and

quilt boulders into their coverlets. Jean was rejected as "old hat."

I matted this collage of Jean’s in a faux marble paper that I made after

she died. I also made the little gold plaque that says, “Jean

Martin after Veronese.”

The collage is 12 x 16 inches.

When Jean's cancer was

diagnosed in summer of 1982, she began to sew large, meditative/symbolic

wall hangings. There was much hope at that time for imagery as a

part of cancer therapy. In the event and in her (our) own case, the

cancer overcame the meditative sewing... perhaps because the world of

imagery and the unconscious is far more complex and devious than we in our

day world know, and also perhaps because when you wish (and there had been

times before the onset of her illness when she had wished she were dead)

sometimes you get it.

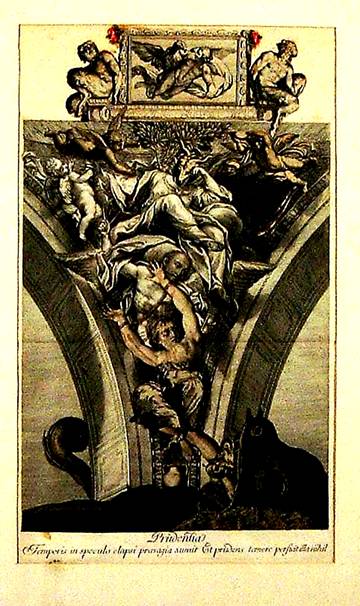

“Prudentia,” collage, 22 x 12 inches.

Made from an engraving of the frescos in the

Farnese Palace in Rome?

If I were to sum up what I experienced

then and I now think and know of Jean's creative life, I think she had

great drive and talent—and in those "creativity studies" terms, she had

fluidity, flexibility, originality and elaboration. What she did not

have was opportunity. Like most women of her generation, care and

love of children and the obligations of jobs and household simply thrust

aside the yet unquenchable need for self-expression. The work would

rise to a great height and then be snuffed out again and again first by

family and second by the art world's own personalities and events and

fashions.

And in that snuffing out I too played

an unwitting role. Although I regarded her art to be as important to

her as mine was to me, I was yet the artist in our family and she was the

amateur. Secondly, and an example of this attitude even in myself,

shortly after we moved into Monte Vista, I decided to move out of what we

had always agreed would be my studio over the garage and to move into the

large basement area. Thus, Jean would have my large space over the

garage to work on her ceramics and sculpture—in fact would have “a room of

her own.” There will never leave the imagery in my mind the sight of

Fredricka scrubbing the studio sink (I had left it filthy with old paint)

so "Mother could move in." About that time, summer vacation began

for school kids and no mother could do anything after work but tend to her

children's demands. In a month or two, I decided the basement was

much too noisy with the pounding of little feet immediately above, that

Jean was not doing anything in the in my old studio anyway, and that I

should move back. She could have for her work space the small

basement storage room at the bottom of the kitchen stairs. We put

her things there and she did not touch them again.

It was a few years later Jean began to

work in collage—by then Demian was gone to UC Santa Cruz and we had a free

bedroom upstairs for her studio—and then from collage she went into

sewing.

Sewing. What a seemingly "paltry,

trivial, women's thing." And what a great battle Jean sewed in the

imaginal world, her allies a winged heart, a flaming torch and a dancing

dragon of gold, her enemy the endlessly secretly proliferating cells of a

breast cancer whose metastatic hunger knew no bounds.

Her life confirmed in me what I already

knew: the great work of every artist is made not in the art world of

museums and galleries but in the secret and silent world of the artist’s

heart.