|

Notes about the role of China and

Chinese art in my work…

(Click the thumbnails for larger images)

The role of China in my life began

when I was a little boy and every Sunday evening for years we went to “The

Chinaman’s” (we called it) for a Chinese dinner. I was adventurous and

once ordered Seaweed Soup in addition to the Chowmein we always had.

|

Years passed, I was in my senior

year of high school and one of the teachers took me under his wing to

learn high culture—the opera, ballet, symphony, 20th

Century British Literature, and Lao Tze. I found a 1910

“transliteration” of the Tao Teh Ching, (now sixty years later I still

have it among my foundation books), made my own more readable

rendition of the chapters that mattered to me, and used it for my term

paper in aesthetics when I was in graduate school.

|

|

|

|

My high school teacher also gave

me a book of ten or so Chinese paintings in color where I noticed but

did not think about all of the inscriptions of poems and owners’ seals

on the paintings; and he gave me a copy of Chinese Art, (pub.

1935) where I found a colored illustration of a Tang “Apple Blossom”

vase.

Somehow there came to me then

the phrase “That this light which once so fell on it should ever so

fall, even to the final dust.” That vase and phrase—and that one might

write poems on the surface of a painting and that I should remember

what Lao Tze said about the void—have been among the foundation stones

for my art ever since. |

|

...but it wasn't this ink stone nor these brushes |

I enrolled as

a Freshman at UC Berkeley in the fall of 1945. Our second semester

introductory art course involved using a Chinese brush, ink stick and

stone to make what our teacher thought was Matisse but, since I had

seen some Chinese calligraphy in the Burlington catalog, I thought was

maybe calligraphy—anyway, wiggly lines. A year later while in a highly

charged emotional state, one afternoon I made wiggly lines until they

made of their own accord the image of what was then my psychic crisis.

In 1947I had wandered in my Sophomore year into the realm of Abstract

Expressionism before the style and the term had been invented. |

|

Soon enough,

my Berkeley Art Department hired a fugitive German scholar to teach

Asian Art History and I took his first course in Chinese art. All I

remember was memorizing the names of Shang and Zhou bronzes and that

we saw them only as miserable postcard size black and white photos. If

there were paintings, calligraphy or ceramics in the course, I don’t

remember them. What a turn off. Afterwards, we all went back to

copying Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso. |

|

|

Other Chinese

influences from my undergraduate years at Berkeley were a course in

Chinese poetry where I learned of Tao Yuanming and his Peach

Blossom Spring and a poem I think called Return, and of Tu

Fu and his poems of exile, nostalgia and regret. I also took that year

a course in Chinese philosophy from Han to Sui taught by a professor

visiting from the University of Peking (it was spring 1949, I’ve

always wondered what happened to him afterward), and a course in

Buddhism from an old German professor who had known Sir Aurel Stein

and showed dingy hand colored slides of Dun Huang. |

|

|

|

|

In the year

after I graduated from Berkeley, I took a course from David Park who

suggested when I was stuck in a painting and did not know what to do,

“Pick the part you like and paint everything else out.” I did that and

found large blank spaces which soon enough I characterized as Lao

Tze’s “void”. When later I saw Ma Yuan’s work, I knew I was right. |

Many years passed. I climbed the

ladder of career both as an artist with many exhibitions (all with the

Chinese background described above but mostly invisible in the work except

for the often large “blank” spaces, and sometimes the wiggly lines from

which forms might appear), and as an administrator, ultimately becoming

Vice President for Academic Affairs at the San Francisco Art Institute

(SFAI), where unknown to all but me, the readings I had made so long

before in Lao Tze and Confucius were of help in my service to a community

of artists and students just as they had been a guide for centuries to the

people of China.

Then, in 1986, came the opportunity

to bring a group of students to study at the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts

(ZAFA) (now the China National Academy) in Hangzhou, and for me to travel

to Dun Huang where I had been dreaming of going ever since my

undergraduate days in Berkeley almost forty years before. I joined the

students in their wonderful studies of Chinese painting, calligraphy and

culture and history at the Academy, and in the following years had the

opportunity to go to Putuoshan, Tibet, Huang Shan, the Li River, the Yun

Gang caves and so many other places of Taoist, Buddhist and Chinese

painting lore, mystery and power in the Western mind.

|

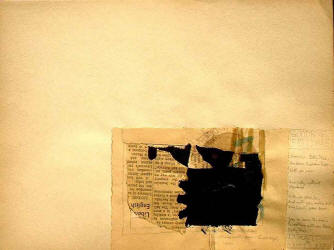

My "Rothko Painting," Summer 1949.

Oil on canvas, approx 30 x 20 in. |

So, in my own

painting, what have I made of all this in the sixty years since it

began? That first painting, the calligraphic wiggles on newsprint in

the spring of 1947, was soon lost because I did not know what to do

with it and knew my teachers had no idea either. Two years later when

I was studying with David Park and painting out the stupid parts and

finding the void in their place, my work often looked like the

painting in Illustration 1. That summer, I worked with Mark

Rothko and calligraphically flowed images of the sunset horizons from

our local Mt. Diablo. Rothko liked it because it was “unknown” (his

guiding word to find the new) to him. Only I knew it was the image of

a picnic and a love affair on the heights of a sunset mountain

|

|

"Goodbye, Betty Mae," 1960

Pencil, watercolor and distemper with collage

on paper, 9 x 12 inches. |

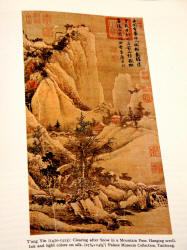

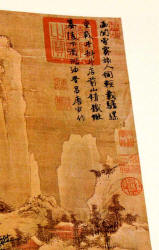

Tang Yin (1470-1523)

Clearing after snow on a mountain pass.

(detail) |

|

Without

really remembering the Chinese paintings with the inscriptions, I

began to write on my paintings sometime in the late 1950’s. I had

always heard the words in my head of the images my hand was making on

the canvas, and sometime 1958-59 I began to work on paper in

watercolor and pencil and collage, and to fill in places that needed

filling with sentences and poems as they came to mind in the course of

the work as in “Goodbye Betty Mae.” I did not

realize then but see now that it’s the way Chinese collectors have for

a thousand years marked the work they love with the poems the

paintings mean to them. Ever since, people have pointed out to me that

what I have written on my work is mostly illegible; but, then, they

couldn’t read the poems on the Chinese paintings either. Anyway and

with that beginning, I went on to write on my work much of the time

from then to now. |

#106 of the large acrylics, June 1970

Acrylic on canvas, 92 x 76 in. |

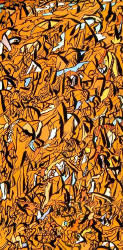

"Orange" from "The Well-Tempered Spectrum"

Acrylic and soft pastel on masonite, 48 x 24 inches. |

|

The “wiggly

lines” modes came perhaps to a climax in 1970-71, first with #106 of

the large acrylics in July 1970 (left above) with the note

to myself that "That's as far as I can go," but then followed a month

or two later with the images of flying mountains and swords and

sunsets as in “The Well Tempered Spectrum, Orange” (right above)..

It’s Mt. Diablo again, but now as far from my home in California as

was my then imaginary Dun Huang. |

.

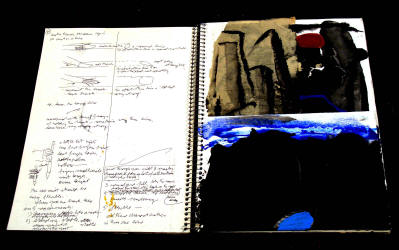

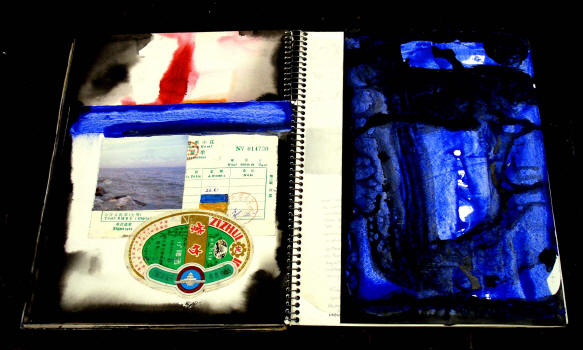

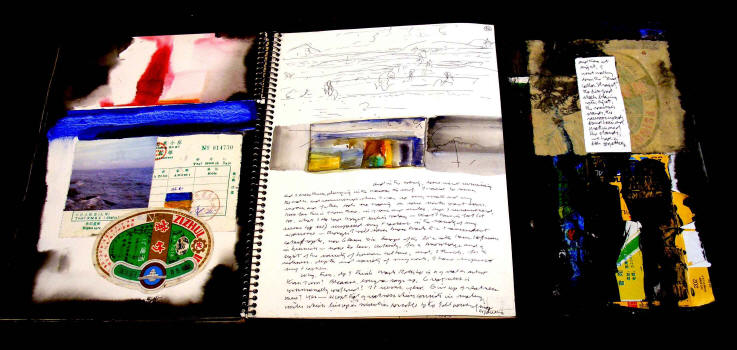

Studio Notes from ZAFA lecture on Chinese

brushes, May 27, 1991. Pen, Chinese brush, watercolor and gouache

with rice paper collage. Page size 12 x 9 inches.

|

In 1986, I began to lead groups of

SFAI students for summer classes at ZAFA, continuing every year or two

until 2000; and I began to make extensive notes not only of the lectures

on Chinese art and philosophy given by the ZAFA faculty as in the

notebook pages on the left, but also continually to draw and

paint and write of the places we went as in the images below from the 1988 notebook from

a trip to Putuoshan, an island in the East China Sea that is one of

the five "Holy Mountains" with many temples and monasteries but also a

submarine base.

|

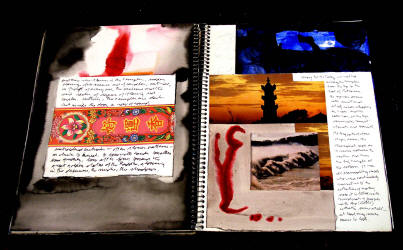

Notebook pages (flap on right side closed

from Putuoshan, May 30-31, 1991.

From the same notebook and using the same materials as above.

|

Notebook pages (flap on right now folded over the

page on left

to reveal the blue flap covering the page on right)

from Putuoshan, May 30-31, 1991.

From the same notebook and using the same materials as above. |

Notebook pages (the blue flap that had covered

the right page now folded to the right

to reveal the page below it and the material on the back of the

flap)

from Putuoshan, May 30-31, 1991.

From the same notebook and using the same materials as above. |

|

# 17, May 2002.

Acrylic with collage on paper, 22 z 15 inches. |

As for the roles of Chinese art and

philosophy, literature and landscape in my work these last few years,

after sixty years of work in art and life, all the things and experiences

in the past come together as a continual shifting of West and East and

past and present—as in #17, May 2002, “Morning” (image on the

left).

“He remembered how sometimes the Chinese scholar—a mandarin like himself

of so much learning, authority and isolation—in the silence of his studio

and surrounded by the tools not only of his first studies but also of his

subsequent social ascent…the brush and ink, the paper and inkstone, and by

curious things and bits of stone his friends of past times had given him,

a water dropper shaped like one of the Taoist peaches of immortality, a

fragment of jade with the lines of the mountains of the Western Paradise.

Thus as for the Chinese scholar to whom sometimes the marks in a rock

showed the path of life, so sometimes for him a stain, a bleed or blob of

paint became his prayer and truth, his words and touch and shining dust.” |

|

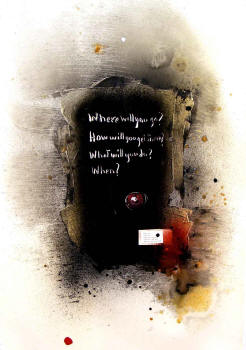

#4, August 2008.

Acrylic on paper with collage, 44 x 30 inches. |

So, in old age as in youth,

experience comes together to form personality—but in old age, we have

accumulated so much more experience. Mine has been broad and now long

thought about—a tapestry of East and West, past and now and tomorrow.

China has given me much, and so have

Italy,

Greece, Crete and

the

Roman temples at Baalbek, the

tombs, mosques and bridges of Iran and Central Asia, the

mosques and markets in Pakistan, the

tombs and palaces, cities and gardens of India, travel to the

Shwe

Dagon in Burma and the Borobudur in Java, and the

mosques and ancient temples of Egypt.

And with the memories of places so

near and so far, there are also the lives of family and friends (some

longer and some less long), and jobs I’ve had and houses where we lived

and all so much and all of it together in each work of art complex or

simple, for it is in the touch of the hand and its place in the image that

all the artist’s life before comes together for now and tomorrow.

And for tomorrow, see #4, August

2008. “Where will you go? How will you get there? What will you do?

When? Tell me, tell me where am I going; tell me, tell me how to save my

life.”

And I marked the height of the

painting with the far star of the goal forever receding, and I marked the

depth of the painting with my own version of the Chinese artist’s jade

seal—my thumb print with Cadmium Red Deep, the color of the blood that never

dies.

—Fred Martin

Oakland, September 2008

|

|