| About my art in 1947-49 (Adapted from my catalog essay in Fred Martin, a Retrospective, 1948-2003, published by the Oakland Museum of California, 2003.) Click the blue links for supplemental images

|

|

First, I am not a painter—an artist—I am a human being. A tangle of body and mind larger than I know. A man of lusts and loves, fears and hopes, a man who felt he had to make his art to know himself and show his art to prove himself, a man who had to build and serve a community of artists so his world would not die. A man who was and is a lustful youth, a husband and father, an old man looking back over a wide landscape—yes, now all three ages at once. I am not an artist (what ever that is) but a me. And, as a me, I made and still make paintings and sometimes books and portfolios of prints that show and express my feelings and thoughts to myself and the world. These are a few of the works I have made to do that. And, before I tell what these works may say, I must tell about my education because that is some of the source of the work I have made and how I have made it. My

education…

I also took a few courses in San Francisco at The California School of Fine Arts during the last semester of my Senior year at Berkeley (spring 1949) and in the following summer and fall. It was that spring David Park taught me the complex in the simple, and that unless your art is first of all for you, why bother? In the summer, Mark Rothko taught me to seek the unknown; and in the fall Clyfford Still taught me “This art has power for life or death. Be responsible.”

The man with the

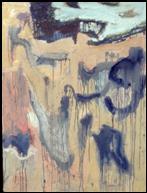

enormous genitals battling a snake, The original work came about in the following way. One fateful noon in late winter/early spring of 1947, I had lunch with three or four very intellectual graduate students who chattered on in a manner that drove me crazy with inadequacy, while all through their talk I heard Katchaturian's Saber Dance pounding throbbing in my head (that year it seemed all of the time on every juke box in Berkeley). Finally, I left the table—I never saw any of those people again—went to the Art Department basement and began to paint with the Chinese brush, the sumi and the newsprint of my Professor Boynton's class the spring before. I blobbed around the way Professor Boynton had taught us to make textures (and I had previously seen some Chinese calligraphy) and there came unbidden beneath my brush in the calligraphic tangle I had made, the image of a man with enormous genitals battling a giant snake. Along with the image came that ecstatic uprush we now call primary process and a whole new mode of artistic making and experience that I had never felt before. As I remember the imagery now (the painting was lost not long after it was made), I know Freud would laugh. Looking at it with my eyes then, it was as great a breakthrough for me as the scream was for Edvard Munch—a painting I then had not heard about (our Art Department art history denied everyone except Giotto and Modern Art from Cezanne to Picasso)—or when a couple years later Jackson Pollock painted his One. Remembering that painting of mine now, it confirms what I've come to believe has always been the purpose of my art: to show the tasks of my life at the times when I must undertake their work. And it was the conflict of my overriding and polymorphous sexuality—as my girl friend had said to me, “ You’ll do it with men, women and dogs” (and even her)—it was the conflict of my roaring sexuality with my sense of life, death and human commitment, the conflict between sex and love—was then my task.

The California

Hills, I pinned the painting to the wall of my room, looked at it for a few days, then put it away and soon lost it. I was not sure what to think of it. The painting was not derived ("abstracted") as I had been taught to do from forms in nature; it was instead only smears of paint made in a moment of ecstatic recollection of oneness with nature herself. Such a work as I had made that night was completely unthinkable for all right thinking people at Berkeley where the most advanced way of working was Picasso's flat-pattern cubism. I now think that summer 1947 painting was an adumbration of what in New York a few years later Harold Rosenberg would call Action Painting and Thomas Hess would call Abstract Expressionism. The arena of my action that night was the painting on which I was working; and so I guess I had wandered into Action Painting. The abstraction that resulted from my actions was certainly the expression of my sexual involvement with the landscape of Central California—so, that little lost watercolor must have been Abstract Expressionist. But I was a sophomore living in Oakland, my teachers were epigones of the School of Paris, and New York was stealing Modern Art from Paris to become for a time the center of the art world. None of this means that I was original. It means that common critical/analytical ways of thinking about art are false. There is no "originating center" for this or that movement, a movement which is then "mainstream" and from which all other artistic activities are trickling ditches. Everything that can happen is happening in many places at once, wherever the souls of the artists need it enough. It is only writers who have not heard of it and so do not write about it and so we do not read about it and so we think it does not exist. But it does, in every soul which cries out.

I had given the painting to Sam Francis when we were students together at Berkeley in 1948-49, and he left the painting with his wife, Vera Francis, when he went to Paris in 1950. Sam and Vera were divorced at some time during the next few years, and I had never thought about nor remembered the painting since—until Vera, now Vera Fulton, called me in April 2003 and told me she had the painting and wanted to give it back to me. It came to late for the show, but is here, as Cezanne wrote on a postcard to Zola when Zola sent him a copy of his novel about artists, “In memory of old times.”

I went with Jean on a picnic to Mt. Diablo one afternoon that summer, the erotic passions fully raging in me (we were to be married the coming January). We had wine, watched the sun set far across the blue ranges of hills in the west, and next day or two I made this painting. We had a critique in Mark’s class, and he praised the painting for its “unknown.” I knew it was my passion in the afternoon but Mark did not. I learned that the “unknown” is in the eye/mind of beholder… and perhaps the artist should keep it there. This learning, however, was in contradiction to what I had learned from my experience of the faculty at Berkeley to whom the things and cultures that drove me and the names of the things I painted and their stories were unknown—and I was just finding out—and so I had to tell everyone what they were so that they would understand my work. It is now (in 2003) more than fifty years later. I still cannot resolve the issue: should I leave the mystery of the meaning and truth of my work the way that Mark Rothko did his, or can I perhaps deepen (or lose) the meaning and truth of my work by (in so far as I can) know and show and tell it here?

As I began the painting back in 1949, I heard the words (adapted from Jung’s Secret of the Golden Flower) "There was a notion common in that age, that it was the flower knew the secret." I painted my golden hills of California with poppies scattered in the grass, rising up towards the right and ever brighter light and all cupped across the bottom and sides in darkness. There was a road zig-zagging up from the dark, and turning ever turning at the center a dark and twisting form from which a few dark drips ran down and in the center of the twisting dark was a small splatch of white. I describe and name these things here—the poppies, the grass, the road—but no one (least of all Clyfford Still) then or now would recognize them. Nor did I then recognize what the whole image was—the union of male and female with the rising light to the right being their future: mine and Jean's. I don't think Still ever saw the picture. Some years later when we lived on Harrison Street, I framed it in 4 in. wide redwood planks and hung it in our large redwood paneled dining room. The painting had become such a fixture on the wall that I forgot to take it with us when we moved. The painting it was lost when the house was torn down after we moved.

|