Fred Martin

A Retrospective, 1948-2003

Catalog illustrations with commentaries...

Catalog nos.

1-26 Click for

Catalog

nos. 30-54

Catalog

nos. 55-63

Catalog

nos. 65-77

Catalog

nos. 78-115

Catalog

nos. 119-137

|

Cat. no. 1.

Sunrise. Spring 1948.

Oil on Masonite, 20 x 24 in.

I thought once there was a necklace in eternity, and our lives the

search for its stones fallen and scattered through time. This

painting is a rectangle showing a sunflower above and a starflower

below. It shows somehow also man on the left and woman on the right

and in the center a binding of them together. A mandala is a circle

usually divided into four complementary/oppositional parts. As if

this painting were a mandala, there are here the union of earth and

sky—and night and day—and male and female that is the whole of myself

living in the world. The painting is the oldest of my works to have

survived—perhaps the first of the stones I may have found from the

necklace in eternity.

|

|

Cat. no. 12. Golden Gate

at Laguna. 1957-58.

Oil on Masonite, 10 x 14 in.

Collection Oakland Museum of California.

For a few autumn months in 1949, I rode the streetcar to work each

evening (my shift was 6pm-2am). One evening I looked at the orange

transfer in my hand, remembered a picture of a Tang Dynasty Apple

Blossom Vase I had seen, thought of the art I hoped to make and

wrote in the back of the book I was reading—“That this light which

once so fell should ever so fall, even unto the final dust.” Ten

years later, I painted the decrepit shells of rotting timbers and

peeling plaster that were the old houses and apartments in the Western

addition of San Francisco. I painted on the spot the way I thought

Corot had made Roman sketches to use in the studio back in Paris, but

I was making Western Addition paintings of the ruin in myself.

Corot’s paintings were souvenirs—to “come again”—of Rome; mine were

the dying light of the rotting city of my soul.

|

|

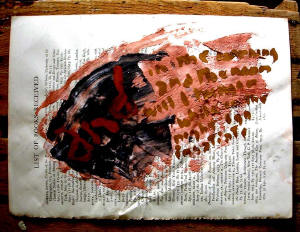

Cat. no. 13c. “And in the

morning…” 1957-8. Texture paint on paper, 8¼ x 12 in.

A place gets into me and I paint it, but after a while there are too

many associations—words, textures, objects, sounds, presences—for a

picture to satisfy them. While I was painting pictures of the rotting

mansions of the Western Addition, we were living in Oakland in a house

as decrepit as any in San Francisco. I tried to hide the cracks in

our house with a paste called “texture.” And soon enough, “texture”

became a paint transmuted into the dirt and dust of the gutters and

abandoned street corners of the Western Addition—“the aurum nostrum

of our dying day” smeared here on art history (The Art Bulletin)

with the knowledge that “in the morning and the noon will I hunger

while in the night I go insatiate.”

|

|

|

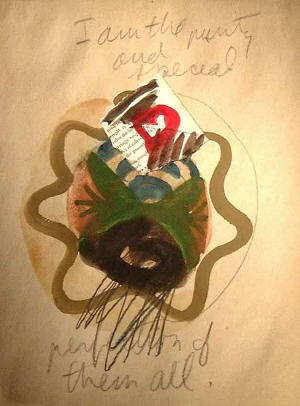

Cat. no. 14a. From the series

“Do you know my name?” 1958.

Watercolor, gouache, pencil, and collage on paper, 12 x 9 in.

After a time I gave up pictures of places and the textures of dusts

that were the dark mirrors of me. To transform, that would be what I

would try to do. I had been reading Jung for years, and even before

Sunrise (cat. no. 1 above), I had wandered in art into what he called

“active imagination.” I asked, “Do you know my name?” and set out in

a quickly evolving series of painting-collages to find out what my

name might be. Jung would have called it Self, someone else might

call it soul, but I think it’s what the Greeks called Daimon.

I did not find my name, but I did receive “I am the purity and special

perfection of them all” (cat. no. 14c) It was not my name but an

image of art to live by.

|

|

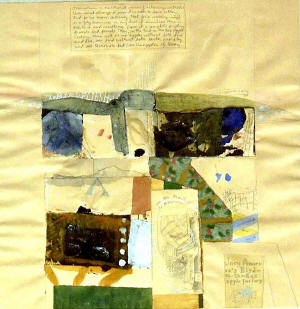

Cat. no. 18. Goodbye,

Betty Mae. 1959. Watercolor, gouache, pencil, and collage on

paper, 9 x 12 in.

Every night after work and family, I went to the studio to make

collages. Lots of collages, 9 x 12 inch sheet after sheet to show and

develop the images churning in my head. Whatever concerned me, I made

a collage—and then, because the churning was still there, I made

another collage, and another, and another. Between 1958 and the early

1960s, I made around three thousand of them. One of the churnings was

about loss, my fear as an individual to be lost in the entropic dust

of the forgotten dead. Betty Mae was one of those lost. One night I

made this collage in her memory “…on down to nothing with you now.” I

guess that in order to save me, I gave to her what I feared for me.

However, she was not, nor will I be spared “…on down to nothing with

you now.”

|

|

Cat. no. 21. Joey America.

1964.

Watercolor, gouache, pencil, and collage on paper, 18 x 18 in.

Collection Oakland Museum of California

As the years 1961 through 1965 passed, the little collages grew into

bigger ones. Thoughts that grew over many collages now grew all

through one collage. And the churning concerns were, yes, still sex

and death, but now in the form of family and the course of the

generations. I was “Joey America” (it was Pop Art time and names like

that were in the air); my wife was “Venus Genetrix” (I had been

reading about Rome and Virgil and his Georgics); and in my art

I set out to build the Western Homestead of past and now and forever.

I was no longer a wanderer in the dying streets of a Western Addition;

I had become the Good Husbandman of a homestead in Rainbow Land.

Stones from a necklace? In these years I found and shaped the great

shining medallion of the center, finally making it into the book

Beulah

Land

(see cat. no. 118, below).

|

|

Cat. no. 26. From

the Carpenter Series, Untitled. 1966-67.

Gouache with pastel on paper, 24 x 36 in. Collection Oakland

Museum of California.

In

1965-66, I did nothing but draw and etch that place I called Beulah

Land. I wore out the imagery and my hands were cramped and my arms

stiff as sticks. What to do next? On the long Labor Day weekend of

1966, I went to the studio and with the words from a then popular

song—“If I were a carpenter, would you follow me anywhere, would you

have my baby?”—set out to paint like a rough carpenter using his arms

to hammer together the studs and rafters of a house… and to have

whatever baby my art might give. I made hundreds of these paintings.

The cannons of the phallus, the pyramids of Egypt as the granaries of

Joseph (an old myth I had read), and the far mountains whence spring

the four rivers of paradise (from a sixth century mosaic at Sts.

Cosmas and Damiano in Rome). Those mountains and rivers have stayed

with me forever.

|

Click for

Catalog

nos. 30-54

Catalog

nos. 55-63

Catalog

nos. 65-77

Catalog

nos. 78-115

Catalog

nos. 119-137

|