Fred Martin

A Retrospective, 1948-2003

Catalog illustrations with commentaries...

Catalog nos.

30-54

Click for

Catalog

nos. 1-26.

Catalog

nos. 55-63

Catalog

nos. 65-77

Catalog

nos. 78-115

Catalog

nos. 119-137

|

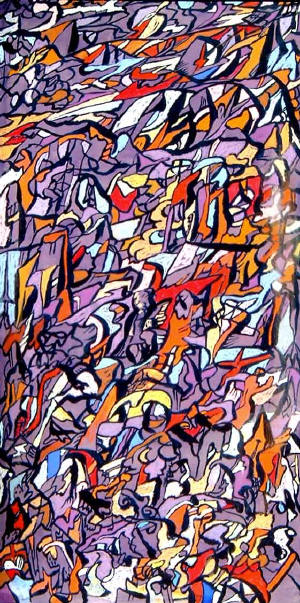

Cat. no. 30. #18, Harvest

on the Mt. Veeder Road, September 16, 1967.

Acrylic on canvas, 66 x 92 in. Collection Oakland Museum of

California.

I had been painting the Carpenter paintings for about a year

when I took forty or fifty of them to show to my then New York art

dealer. He did not like them; and on the plane on the way home, I

read in Darby Bannard’s The New Art something like “the glory

of American painting is its majestic size.” When I got home, I

rearranged my small studio to paint majestic size. If size made the

big boys glorious, maybe it would do it for me. I began to paint the

24 x 36 inch Carpenters as repeats all over 66 x 92 inch

canvases. Then I saw the quinces ripening on a tree in our backyard,

and I went back to Beulah Land—but as large as “the glory of American

painting.” One late summer afternoon, I went looking for an artist I

knew who had moved to Mount Veeder Road somewhere near the Napa

Valley. I did not find him, but came home and painted Cat. no. 30 as

the result.

|

|

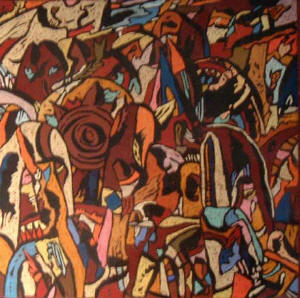

Cat. no. 31 #25,

Large Corn Sheller Wheel, January 5, 1968.

Acrylic on

canvas, 66 x 92 in.

I found a curious object in a junk store in Sonoma County. It was a

tool with a toothed wheel to tear the kernels from corn cobs to make

cattle feed. I had made images of corncobs loaded with corn as

phallic symbols of fertility; and in this wheel I found the image of

all the pain of family life. I made many drawings of the “corn

sheller,” and then made this big painting of its toothed wheel as an

object hung on an A-frame in a barn for everyone to see. I carved the

top of the frame with a heart for love and pounded into it a nail for

the husband and another for the wife… nails forever inextricable in

the wood of the A frame of the family tree that holds the wheel of

life in the barn of the Western Homestead in eternity. And as for the

shining medallion at the center of the necklace in eternity, there’s

no great beauty without fear and no great love without pain.

|

|

Cat. no. 32. #54, Johnny

America Still Life, November 9-11, 1968.

Acrylic on canvas, approx 66 x 92 in.

Collection Oakland Museum of

California.

I had made many big paintings to make me glorious, but I began to feel

that the imagery was too fixed—like the melody of a folk song instead

of the complex variability of a symphonic theme. One summer afternoon

in 1968, I saw what seemed to be a half nude man coming up out of Lake

Merritt. High cirrus clouds were curling in the sky above his head.

That night I decided whenever a form in my big paintings started to

close like a folk melody I would break it with another form only that

form would be broken in turn. Out of that streaming of broken

forms—the “primary process” speaking from the unconscious—I would then

use all my art-craft to make a whole out of parts. Looking back, the

man coming out of the lake was my “primary process” saying “LOOK AT

ME,” and the curling cirrus in the sky was the streaming of my art to

come.

|

|

|

Cat. no. 40. From Dust of

Paradise Harvest, The Well Tempered Spectrum: Violet. 1970.

Pastel and acrylic on Masonite, 48 x 24 in.

Collection Oakland Museum

of California.

In the summer of 1970, I had been using acrylic for four years and had

yet to find a way to develop color like a composer might orchestrate a

symphony from a piano score. (The symphonic was then my visual

ideal.) After the 106th acrylic of “majestic” size (cat.

no. 48 in this show), I got real about scale—smaller—and switched to

colored sticks of soft pastel so I could hold a rainbow in my hand.

I kept on with the streaming lines of the big acrylic paintings, but

I filled the spaces between with the soft pastels. I called the new

work The Dust of Paradise Harvest, and I made a

Well-Tempered Spectrum (remembering Bach’s Well-Tempered

Clavier). This Violet is the last of the spectrum

series. The whole series showed the mountains of paradise, the heart

from the Western Homestead, and the winged sword of my masculinity—all

in the streaming of colors of the waters of life.

|

|

Cat. no. 41.

Afghanistan. 1971.

Pastel on Masonite, 18 x 18 in.

Late in

1970 I learned I was to receive an NEA grant for any purpose of my

choice. I had been reading Mortimer Wheeler’s Splendors of the

East and chose to see the places in the book by traveling around

the world. I was making work in the manner of the streaming of the

late-summer 1970 Dust of Paradise Harvest series, but by winter

that year I had begun to make images of specific places of my

imagination, like this Afghanistan, which came from reading of

the Kingdom of Prester John, the mythical history of Alexander and

the gates they said Alexander made to save the West from the violent

tribes of Gog and Magog. My trip around the world in the spring of

1971 began before I had finished this painting. I was proud that I

was able to complete the painting when I came back six weeks later.

|

|

Cat. no. 45. #83,

September 7, 1969.

Acrylic on canvas, approx. 92 x 66 in.

The necklace in

eternity and the mountains beyond the far horizon are eternal time and

infinite space. But I was painting in our finite world of passing

time. The ancient Iranians had a god, Zurvan, the god of “the

time of long duration” and of the vast and time swept deserts of

Iran. The Gnostic god of time was Aion. He had the head of a

lion because time eats everything. He had wings because time goes

everywhere. He was wound with a snake carved with sun, moon, and the

five planets for time’s fatality. What has that to do with this

painting? I was imagining the plains and mountains of Central Asia

and the old old land of Zurvan with Aion ravaging through its

ruins. And I saw there a golden tree with singing birds that was my

love for my wife and our lives together in time. Stones from the

broken necklace are everywhere if we can see their shining.

|

|

Cat. no. 54. My Hands in the Sun. 1971.

Oil on Masonite, 18 x 18 in.

I made slides on the

trip around the world because I did not think I could paint while

traveling—in the 1980’s, I learned I could (see cat. nos. 124-128). I

did not know how to use the slides when I got back, but I was sure I

had to quit the “streaming” pastels of before the trip. I went to oil

in order to show as clearly as possible what most mattered to me. The

first of the “matters most” was a painting of some poppies growing in

a cracked sidewalk just down from our house (cat. no. 51). And then I

began to make my body—my torso better built than I was (cat. no. 52),

my solar plexus with a tattoo that I do not have of a sunrise heart

(cat. no. 53), and then my hands raised in the sun. The hands wear

the ring I still wear. I made the ring into a golden mandala with

four small diamonds when I married Stephanie Dudek thirty years after

this painting was made.

|

|

|

|

Click for

Catalog

nos. 1-26.

Catalog

nos. 30-54

Catalog

nos. 55-63

Catalog

nos. 65-77

Catalog

nos. 78-115

Catalog

nos. 119-137

|